Q&A: The essential, yet underappreciated role of acoustics in Architecture

If you’ve ever put on headphones to focus in a noisy office or noticed your voice echo in an empty apartment as you move into a new apartment, you’ve encountered the invisible dimension of architecture: acoustics.

Acoustics play an essential but often underappreciated role in architecture, taking a backseat to the things that are tangible and visible. Thea Larsen, a civil engineer with expertise in acoustics, works in the Henning Larsen Research team to advocate for better sound quality in every project and develop tools that can help “visualize” the invisible.

How did you become interested in acoustics?

When I was young I wanted to play music, but I’ve got a horrible sense of rhythm – I have a quite good pitch, but I can hardly clap in rhythm. It’s horrible. I slowly realized that if I combined my interest in physics with my interest in sound, I could avoid the whole rhythm thing.

When I would sing in big concert halls, I started noticing how space affects sound and acoustics in the choir. But it’s not just in these formal spaces - have you ever sung in the bathroom? It’s the best! The reverberation is great because of all the tiles and hard surfaces. As I noticed how great it was to sing in places like concert halls and bathrooms, I started to consider that sound quality must have something to do with the room.

I had actually wanted to be an architect when I was younger, so I just combined that with my interest in music and in physics, and that’s how I ended up here.

How do you explain what you do to someone who is not in architecture?

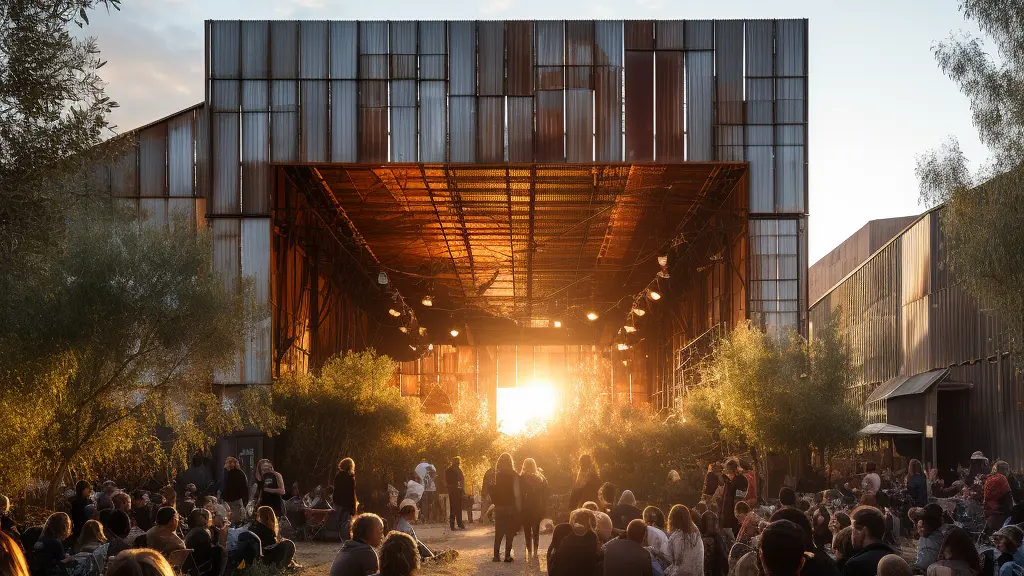

As an acoustician, my job is to ensure that the acoustic environment works. For example, when you get into a church you can feel that it’s very reverent place. There’s a spiritual feeling within and that’s largely because of the acoustics. In places like this, the space has typically been designed to support that kind of experience. By contrast, if you are in a cinema, there’s almost no reverberation at all. If you try to talk to someone a distance away, they might not hear you. I work within that spectrum; between the reverent church and the shushed cinema, so to speak, to make sure that the acoustics within a space suits its intended purpose.

Can you give an example of bad acoustics that we’ve probably all experienced?

I used to be an acoustic consultant and a very common problem that I encountered came from families who had moved into newly-built houses. A lot of these combine the kitchen, dining, and living rooms into one conjoined space and have high ceilings and a lot of hard surfaces: walls, cabinets, tile floors. When everyone was using the space, the family would be miserable: people are talking, kids are crying, parents are making noise in the kitchen and it all blends into an overwhelming noise. I think most people have experienced something like this, being in a space where the noise just bounces around and builds up and becomes confusing and agitating. This is especially bad for people with hearing disabilities, particularly if they wear hearing aids.

Is it unusual for acoustics to be applied or researched within architecture?

I think architects can be very focused on just the visible, tangible things. Acoustics are obviously invisible. When you sit as an architect and have to decide between installing acoustic absorbers or placing skylights in a ceiling, you’ll usually choose the skylights. That means acousticians often come in after a building is built to fix or readjust the acoustics, which isn’t ideal. It’s much better if acousticians can be a part of the design process from the beginning so we can all get the best of both worlds: skylights and acoustic paneling, for example, and having acoustic panels being a part of the visual design.

Are there other key advantages to integrating acoustic design early in the process?

For me, it allows me to be more confident that users will be happy. At the end of the day, that’s the idea of designing interiors – creating spaces where people will be comfortable and happy. But it allows us also to nudge users to make greater use of the spaces we create for them. If a canteen has bad acoustics, people may take their lunches down and eat at their desks. Then we miss the conversation we would have had, not to mention the great ideas or new connections that might have come up. If a meeting room has bad acoustics, people will rush through meetings and be less focused, because they’re not comfortable or cannot hear the speaker. Then it’s not really a productive meeting. You can see how good design and functionality like this translate to productivity and comfort. If my end goal is to make people happy, I can do more if I start in the beginning.

How can you tell how the acoustics will perform before the building gets built?

That’s largely a matter of experience (laughs). But my colleague Finnur has been working with acoustics in virtual reality – he’s developing a tool that would simulate experiencing a space in real-time. It allows a user to test how space’s acoustics change depending on what types of absorbers you use and where you place them. For me, it’s really important to know how space will be used, for what functions, and where people will be so that I can shape the acoustics accordingly.

We also have a digital tool that allows us to make acoustic projections. We lay out space, determine where absorbers will be, and the tool gives us a reading on reverberation time, sound clarity, and the speech transmission index (essentially how far sound carries.)

What is it like to collaborate alongside other specialists in the Ph.D. program at Henning Larsen?

When we combine our abilities and specializations it helps us communicate new ideas and specialized knowledge to the design teams. It would be great to have a standardized system, say with virtual reality, where we can really show architects how a building will feel, look, sound, and so on as we design it. That’s a big advantage, and one I think all of us in the program can contribute to.