Notes from the field: designing the ‘sensitive city’

By Maya Shpiro

We’re living in a time defined by digital overload, environmental strain and growing social fragmentation, where technology connects us virtually but leaves us physically apart. In this landscape, public space carries a new weight. Public urban spaces are still one of the few shared places we inhabit, making it more important than ever to design them with sensitivity to the human experience.

Contact

Social Impact and Co-creation Lead

Design can’t solve disconnection on its own. But it can shape environments that encourage participation and belonging.

What does it mean for a city to really listen to its people? And how can urban design answer that call? Alongside Philippe Larocque and Søren Øllgaard, we recently contributed to the conversation at SenCité, the First International Conference of the Sensitive City in Lyon. Unpacking an evolving concept rooted in empathy, inclusion and emotional connection, we shared ideas on how cities can respond more intuitively to the people who inhabit them.

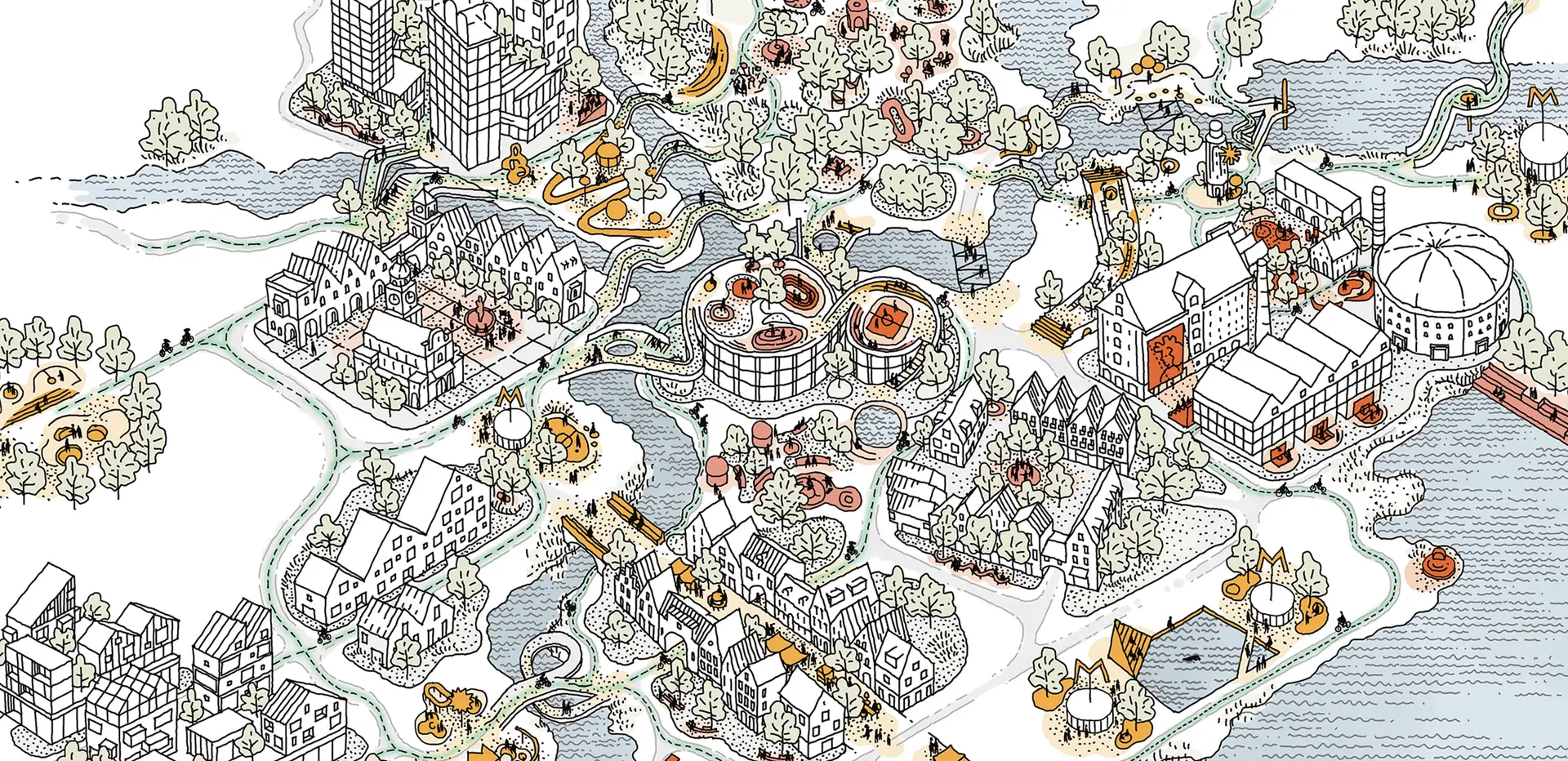

A sensitive city is one that welcomes people with safety, accessibility and spaces that stimulate the senses, without overwhelming. It is open and designed for the freedom to participate in public life on one’s own terms. It reflects the diversity of its communities and accommodates difference, not by eliminating tension, but by making space for it.

Designing for the sensitive city means creating subtle invitations for connection: a bench positioned for conversation, a patch of garden tended by neighbors, the sound of children playing. These everyday moments are the antidote to the flattening effects of hyper-efficiency and sameness that risk erasing urban identity.

A sensitive city is not static or complete – it’s a fundamentally dynamic place that is alive, evolving and committed to both people and place. A work in progress, by design.

Lessons from Copenhagen

Living in Copenhagen over the past few years, I’ve noticed how the city is designed for movement and connection. Named the world’s most livable city in 2025, Copenhagen offers a real glimpse into what a sensitive city can be.

Copenhagen is truly a cycling city. You’ll see all kinds of bikes and riders, from racing bikes speeding by to cargo bikes carrying three kids, or even tricycles for those less confident on two wheels. This creates natural moments of recognition and small connections that simply don’t happen when everyone is enclosed in cars.

The city also makes the most of every outdoor space, prioritizing public areas. Streets transform into plazas, school playgrounds stay open most of the time, green spaces are full of life, and the waterfront is approachable and accessible, keeping us connected to nature year-round.

Its mix of uses – social housing beside high-end homes, churches converted into community spaces, skateparks next to pétanque courts – creates authentic, everyday overlaps that make Copenhagen feel welcoming and real.

To understand a sensitive city, we need to observe how life and connections unfold naturally. Equally important is how these spaces are shaped from the start.

A design that listens

Designing spaces with empathy means listening closely to those who will live and move within them. Every project, every line drawn, is an opportunity to listen more closely and represent more people. We also extend this opportunity to the natural world, as illustrated in our recent publication, Design as Water. This begins with asking what it would mean to design with water as a key stakeholder, rather than something to solve.

“In many ways, nature-based design, as explored in the Design as Water paradigm and the sensitive city, are two parts of the same current,” said Philippe Larocque, Project Manager, Senior Landscape Architect. “Both call for cities that are responsive, fluid, rooted in care. Instead of imposing rigid systems, we’re invited to design with more humility — to listen to local knowledge, to ecosystems, and to each other, and by doing so, we can co-create conditions that support life in all its forms.”

This also echoes through my work with Urban Minded, a research-driven initiative exploring how teenage girls experience public space. I’ve seen how daily urban interactions reveal deeper patterns of inclusion and exclusion.

In Copenhagen, we walked alongside the girls, letting them lead us through their urban routines. Their honest insights showed us which spaces made them feel safe, seen or excluded. What stood out was how spaces that felt both familiar and a little unexpected helped build confidence and connection.

Now, in Esbjerg, Denmark, we’re bringing this learning to life. Together with the girls, through workshops and ongoing dialogue, we’re shaping a new urban space that redefines play — not just as playgrounds but as a catalyst for creativity, connection and community. By centering on lived experience, we aim to create a city center that supports mental well-being and includes those too often overlooked.

The sensitive city should be measured by its ability to let diverse people get to know it and form relationships with it, but also for those relationships to remain alive and changing, balancing the comfort of the familiar with the intrigue of the unknown.

In the Faroe Islands, we adapted Urban Minded to a new context – higher education. Working with students, faculty and neighbors at the University of the Faroe Islands, we helped design a timber Community Building in Tórshavn. Here, architecture and programming evolve in response to real needs, creating a civic hub that belongs to everyone.

1970