How the classroom is evolving past physical boundaries

When higher education can take place on a mobile phone, the way we think about the physical classroom is changing. Partner Signe Kongebro shares her insights into the classroom of the future.

Our idea of learning no longer lives in a one-room schoolhouse. Education has transcended physical boundaries: We can now pull up a classroom on a smartphone screen during a bus ride, or earn a university degree in bed on a laptop. As we react to changes in how, when and where we learn, we must consider the form and function of physical learning spaces in the future.

As education moves beyond the classroom, it challenges conventional ideas of what constitutes a learning space. According to Henning Larsen Partner Signe Kongebro, who heads many of our academic projects, establishing a distinct architectural identity will become an ever more important challenge.

Emphasis on identity

“In the past, buildings were clearly part of a campus or beyond it. Today, those borders are more fluid,” Kongebro says.

“We are seeing a greater need to create a destination, because there is so much competition in learning and who can provide it: Free online learning, organized online learning, alternative community classes, and competing universities. Campuses need to be attractive and they need to give something more to students, researchers and visitors, something beyond just learning and education.”

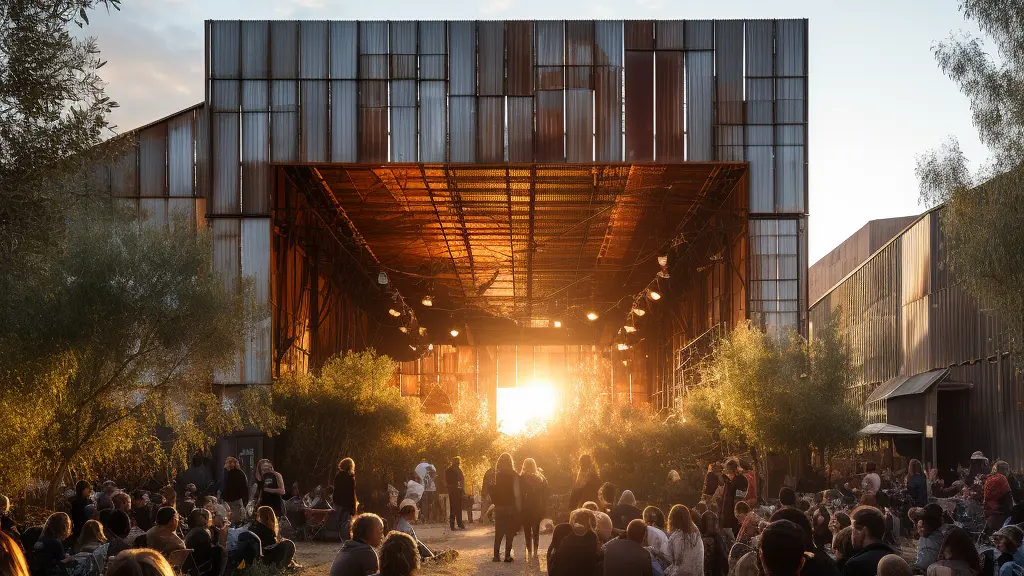

Especially in urban settings, the boundary between an institutional campus and the surrounding city is blurring. When campuses grow where space is scarce, they must adapt learning spaces and teaching methods to existing spaces, reimagining classroom models in atypical typologies.

Learning on personal terms

The learning model of a teacher steering a class from the front of the room is increasingly abandoned in favor of more collaborative, democratic structures. Breakout groups, collaborative tables, and decentralized learning are key elements of this new learning model. In effect, this gives more agency to individual students. As we recognize individuality through the physical structure, we can reflect on how our spatial design can better accommodate individual needs and preferences.

“Some people are very active learners, while some people need to sit, reflect, and take it all in. It’s so important that we’re aware of who is in our learning spaces, and to design for them,” Kongebro says.

“It seems designing learning spaces is less about designing for education, but rather thinking about the things that constrain or support education, and really designing to support those things. When you’re comfortable or feel safe, you’re so much more open to new ideas. If you’re in the opposite position, you can’t. There’s a fundamental idea of comfort and respect that needs to be taken seriously.”

Finding intuition in materials

Designing learning spaces is an exercise in wayfinding, in personal user experience, in considering how the building meets the user on their own terms. Especially in early education, Kongebro explains, classrooms are evolving to value the important relationship between bodies and learning spaces.

“A good learning space is intuitive. It is a space where you can learn from the building, where the building itself is a teacher. Especially for young students, it’s important that the whole process is part of it. It’s not just the mind that learns, but the body as well,” Kongebro says.

“There should be dignity and intention in the materials, and in how the body meets the building – how a door handle works, how a staircase works, what can you use a window for. It should not be a building with a manual.”