Can we decode design?

A lot of creative companies are putting great focus on machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data availability. But should we be afraid of the design process becoming fully automated?

A lot of creative companies are putting great focus on machine learning, artificial intelligence, and data availability. But should we be afraid of the design process becoming fully automated?

Computational Design Architect, Iliana Papadopoulou thinks not:

“I believe that the successful integration of new technologies will see the enhancement of creative thought. At Henning Larsen, we are unfolding the potential of generative design as an enabler for more sustainable solutions.”

But wait… what is generative design?

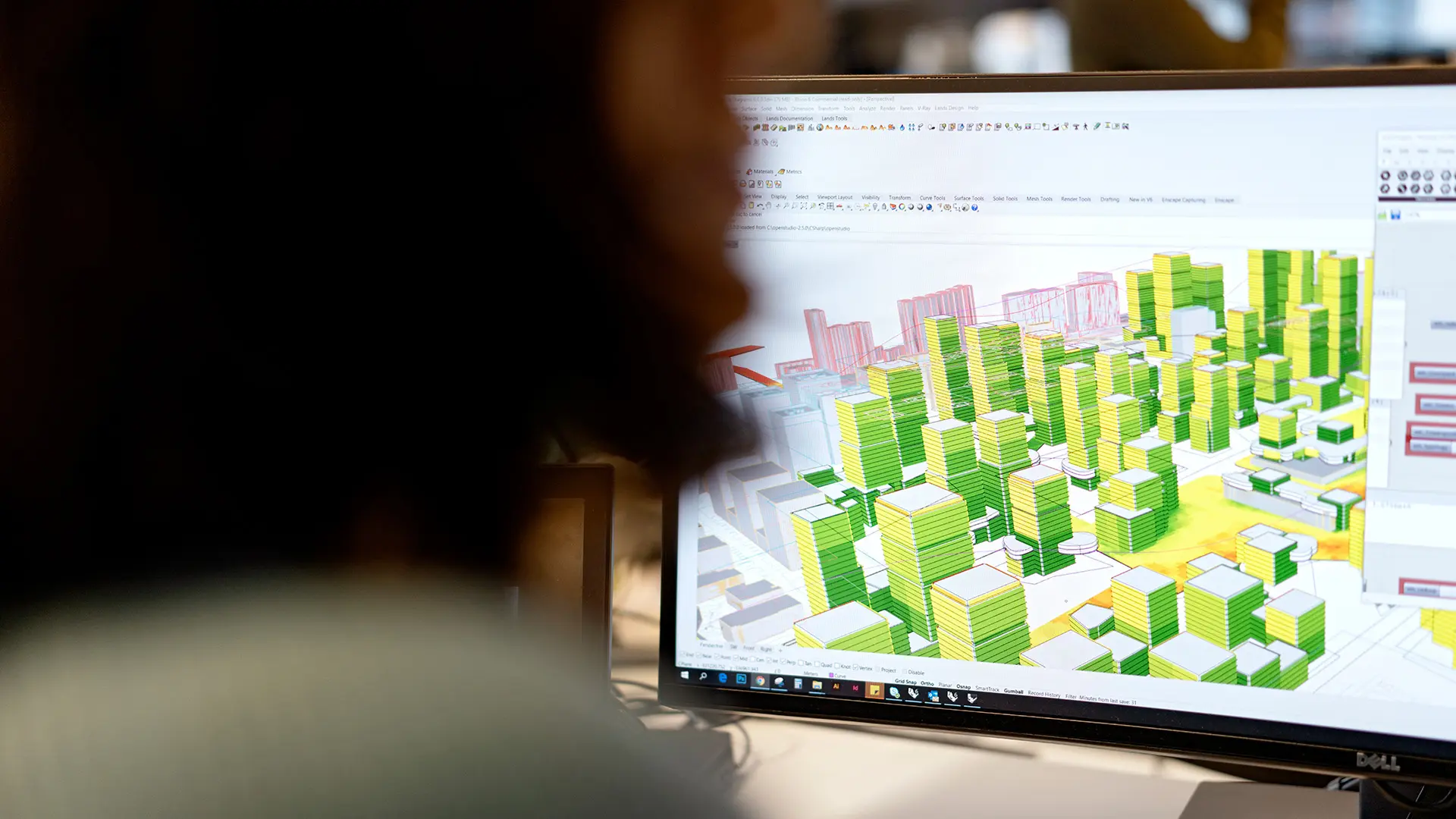

Generative design is a digital process of iterative design exploration. You input design goals into the software, along with parameters such as zoning restrictions, spatial requirements, materials use, energy consumption, CO2 footprint, and cost constraints. The software then explores all the possible permutations of a solution, quickly generating design alternatives. This process iterates through an array of design proposals, sort through the iterations, and identify the best ones, all while providing detailed analyses for each proposal.

“In the time you can create one idea, a computer can generate thousands along with the data to prove which designs perform best. As the designer, you still define the parameters, but instead of modeling one thing at a time, computational or generative design software helps you create many solutions simultaneously and sometimes even find unique and unforeseen solutions that would be difficult to discover with traditional methods,” explains Iliana.

There’s no limit to the scale or type of design challenge this process can take on: from determining how much area to cover with minimal environmental impact to fitting as many worktables in an office as possible without losing good circulation, the process is equally efficient.

In the AEC industry, the application of generative design methods is typically geared towards streamlining the traditional workflow. But generative design’s greatest potential lies in its ability to support sustainable architecture by reducing the use of our resources.

Where can it be applied?

Generative design can be used in all scales – from big masterplans and unique façade components to low-practical atomization processes, like those concerned with new mobility.

“For our new masterplan ‘Coop Byen’ in Copenhagen, we developed a new generative design tool to inform the design process. As a result, we found that by densifying the structure, we could improve the urban comfort, wind environment, and daylight conditions while at the same time also freeing up more room for green spaces.

In Boston, we are designing a new Mixed-Use Office and Performing Arts Center in the city’s Seaport District. The design is inspired by the coastal climate and the dynamic qualities of the sea. The ambition here was to both reflect the natural environment while also making the most of it. Combining sun, daylight, and wind analysis with a generative study of passive façade shading, we are able to optimize orienteering, sizes, and placement of the fins and louvers. The goal was to find the best solution for indoor environment (daylight), energy consumption (reduced cooling load), and use of materials. The solution turned out to be a façade incorporating a shading solution that morphs across the envelope and is adapted to the specific orientation.”

Is generative design a standardized process?

For each case, the team could run between 10-20,000 options. However, this is not a standardized process.

“Initially we’ll make a script as agile as possible with clear goals, and then for each project, we’ll tweak and customize it. The result is an algorithm that is intended to suit both project and process. It is important to understand building up the script, case by case, as a design exercise in contextual architecture, equal in importance to the traditional sketching process.”

In this approach, the computer becomes an active collaborator in the design process, not just a repository for data. Relieving the designer of the responsibility of all iterations, the computer can propose multiple design alternatives and classify them according to prerequisites and premises designated early in the process.

“We recognize that our computational design systems have potentials and limitations, the same way a pen has, in drawing an analog sketch. What we are focusing on, is pushing the boundaries of these potentials and reducing the limitations.”

Though computers can organize and prioritize decisions for designers, they cannot make them on their behalf. The role of identifying and defining problems as well as the factors for their solutions cannot be outsourced to technological systems. Comprehending needs, values, problems, and possible solutions deeply human tasks in that they demand sensitivity and compassion. Above all, design demands and embodies a willingness to respond to the challenges with which our communities are met, as well as the ability to imagine a better future for ourselves and for others.

A job well done is not defined by the metrics of reduced energy consumption and optimized wind conditions, alone. At large, it is an assemblage of elements that shape experiences. And experiences cannot be scripted.